I am a second generation atheist born in the post-Soviet world and raised in the West, and my immense curiosity about pre-Christian winter solstice traditions makes every December a month of soul-searching. For the lack of a better word, I would describe it as window-shopping: I obsessively research folklore from around the world and imagine myself in all these settings. From Icelandic Jólakötturinn (The Christmas Cat), to Swedish Christmas Goat tradition and Polish caroling - many of them resonate with me much stronger than Christian Christmas.

This past December, my family came over for a dinner to find me obsessing over a popular Ukrainian holiday tale - “The Night Before Christmas or Evenings in the hamlet near Dikanka village”. In English, this tale is simply known as “The Night Before Christmas”, and it’s written by a writer of Ukrainian heritage, Nikolai Gogol.

When the Russian invasion into Ukraine began, I made a series of special issue radio shows analysing historic and cultural background of Russo-Ukrainian relationships, and Gogol was one of the pivotal characters in my overview. In both Imperial and contemporary Russia, Gogol was and still is a contested figure.

Born at the time when Catherine the Great just absorbed some Ukrainian and Polish lands and started intense russification policies, Gogol was one of the first generations of Ukrainians growing up with fragmented identity. After Catherine the Great's edicts stripped non-gentry of the right to own land, Gogol’s grandfather was forced to falsify family records, claiming noble status to avoid losing land and property. Simon Karlinsky, one of the most insightful of Gogol’s biographers, suggests that Gogol’s complicated relationships with his own identity - particularly the impostor syndrome - could be traced to this episode.

The language of Gogol’s household was Ukrainian, but Gogol wrote in Russian, although his prose was full of ukrainisms and his stories - of satirical and endearing, yet at the same time, mystical depictions of Ukrainian rural life. Gogol was born in the Cossack town of Sorochyntsi, which at the time geographically belonged to the Russian Empire. Like many writers of his era, he recognized that greater literary opportunities awaited him in the capital.

When Gogol arrived at St. Petersburg in hopes of better prospects for his literary career, he was not regarded as a “russian”, but as khohol (a derogatory term for a person of Ukrainian heritage), which surprised him and made him self-conscious about his heritage. His stay in St. Petersburg forced Gogol to make difficult decisions regarding his self-identification. The November Insurrection in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had ignited a surge of Russian nationalism, making questions of loyalty and self-definition unavoidable.

At first, Gogol was signing his name as “Gogol-Ianovskii,” a nod to his familial roots. But the hyphenated surname, with its Polish origins, quickly became problematic in the charged atmosphere of the imperial capital. He experimented briefly with the Russianized variant of his surname - “Ianov, ” before abandoning the Polish half of his name entirely. By the latter half of 1830, he had resolved to be known simply as “Gogol.” In a letter to his mother, he insisted she use only this version of the name, citing the rising suspicion toward Poles in St. Petersburg.

This shift was more than personal - it aligned with broader Tsarist efforts to recast Ukrainian identity within the empire’s narrative. While the authorities tolerated Ukrainian folkloric particularism, they urged Ukrainian intellectuals to sever their Polish ties, reframing cultural heritage as a subset of Russian imperial identity. For Gogol, changing his name was a strategic adaptation to a world where one’s literary legacy depended on fitting into the prevailing orthodoxy.

Contemporaries and friends described Gogol as jovial and light-hearted, yet prone to tumultuous temper. However, his struggles with identity - both as a writer and as a Ukrainian national - left their mark, eventually making him more secretive and reserved. There is no doubt that Gogol felt like a stranger among literary socialites of Imperial Russia. He was often put under a microscope, treated both as an exotic other, and as someone who had to consistently prove their worth.

Witches, imps and the stolen moon

I first encountered Gogol in an unlikely setting - the office library of my mother’s academic supervisors. I was ten years old, left to my own devices while the grown-ups, geologists and meteorologists by trade, delved into their kitchen discussions. Finding a copy of Gogol’s short stories among the technical literature of academics was not unusual. In the post-soviet environment, career scientists were often well-versed in arts and humanities.

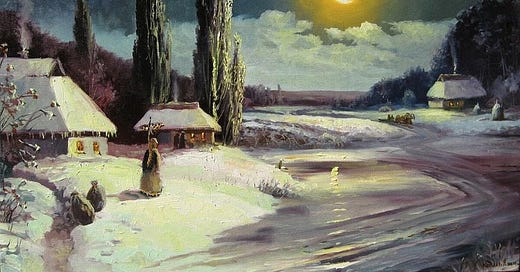

The book caught my attention with its cover - a vivid illustration of jovial flying witches soaring above the village huts in a moonlit sky. It promised mischief and mystery, and I couldn’t resist. Gogol’s humorous, yet mysterious world of rural, Ukrainian gothic was spellbinding. Devils, witches, a stolen crescent moon, forbidden blooms and vengeful drowned brides. Dark creatures of unknowable origins who dwelled in the wild lands beyond the peaceful countryside. Vampiric imps and walking corpses, who made their lairs in the cellars of old churches. The promise of Christian salvation did not hold power over them, and the holy symbolism was only as effective as the resolve of those who wielded it.

Gogol published the first volume of his Ukrainian stories, “Evenings in a hamlet near Dikanka”, in 1831 under the pen name Rudy Panko (what a strange name indeed). The collection was an immediate success, and so the second volume followed in 1832. By 1835, Gogol had released two more collections - Mirgorod and Arabesques - which solidified his place in the literary firmament.

During this period, Russian editors and critics framed Gogol as a distinctly regional writer, whose work captured the unique essence of Ukrainian identity. They used his stories to illustrate the national character of Ukraine, portraying its cultural quirks and local color as a complement to the broader Russian imperial narrative.

After the success of his initial publications, Gogol became deeply fascinated with the history of the Ukrainian Cossacks, a passion that spurred his attempt to secure a position in the history department at the Imperial University of Kiev. He had powerful allies from the literary world and the ministry of education who were willing to vouch for him, yet, despite their support, Gogol was dismissed as unqualified. Frustrated but undeterred, Gogol channeled his passion into fiction, producing Taras Bulba, a tale inspired by the history of the Zaporozhian Cossacks.

It is important to note that one of the key policies of Russification during this time was making the Russian language mandatory in Ukrainian educational and governmental institutions. This was partially enforced by appointing Russian nationals (who did not speak Ukrainian) to key positions in government and universities. It is likely that the effort to keep Ukrainian “nationals” from the posts of cultural significance was the reason for why Gogol’s candidacy was rejected.

In 1834, Gogol was unexpectedly appointed Professor of Medieval History at the University of St. Petersburg - a role for which he had no passion or qualifications. Predictably, this ended poorly. One year later Gogol had resigned, marking the end of his short-lived academic career.

Gogol’s university years, and the period that followed shortly after his resignation proved to be productive for his writing. Russian critics reclassified Gogol’s as a distinctly Russian writer, contradicting earlier assessments that had emphasized his regional roots.

Dead Souls

The death of Alexander Pushkin, Gogol’s friend and perhaps the most influential Russian poet, left a profound mark prompting Gogol to further immerse himself into writing. Under this influence, Gogol undertook his most ambitious project - the satirical epic Dead Souls.

Although Gogol’s work was always satirical in nature, it is with the publication of Dead Souls (under a censored title The Adventures of Chichikov) that Gogol's contemporaries came to regard him as a great satirist who lampooned the unseemly sides of Imperial Russia.

Gogol referred to Dead Souls as a poem, despite its prose form. The protagonist Chichikov journeys through circles of hell, reminiscent of both Dante’s Inferno and the myth of Odysseus wandering from one chimera to the next. As Chichikov’s adventures unfold, so does the critique of Russia and the Russian mentality.

Dead Souls is considered the pinnacle of Gogol’s work - and a map for understanding the so-called Russian soul, with the character of Chichikov representing Russia itself. A man driven by a shrewd, calculating nature, Chichikov aims to purchase as many “dead souls” (deceased serfs still on tax records) as possible, thus revealing his talent for exploiting systemic corruption. His motivations stem from a relentless desire for wealth and status, rooted in his upbringing, and by acquiring dead souls, “on paper”, Chichikov appears more wealthy and influential than he is. Chichikov masquerades as a respectable gentleman, using charm and appearances to manipulate landowners and officials, embodying the moral decay within Russian bureaucracy.

Gogol envisioned Dead Souls to be a trilogy, however, the next two parts of the epic never saw the printing press. The writer suffered from a spiritual crisis and ill-health. For three years, he oscillated between writing the second part of his masterpiece and wandering across Europe in search of a cure, chasing elusive remedies for his maladies. In 1845, in the midst of his spiritual crisis, Gogol burned the draft manuscript of the Dead Souls Part II he was so diligently working on. He would burn yet another draft of the manuscript in 1848.

One of the theories for the enduring spiritual crisis is that as a writer, Gogol felt an immense responsibility to change Russian society through his art. And in his own eyes, he was failing, blaming himself to be not a good enough writer.

Gogol’s life took an even more tragic turn after his return from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1848, when he formed an intense friendship with a fanatical spiritual elder Archpriest Matvey Konstantinovsky. Konstantinovsky condemned Gogol’s work as sinful, instilling in him the fear of damnation. He was the only person who read the second part of Dead Souls, after which he criticized it as harmful, urging Gogol to destroy it. Konstantinovsky advised Gogol to commit to ascetic practices of self-denial and abstinence from worldly pleasures in order to “cleanse” his soul. These practices further weakened the writer’s health, and he fell into a deep depression. Succumbing to the mounting pressure from Konstantinovsky, Gogol burned the second version of the manuscript, after which he took to bed. He stopped eating, and nine days later he died of starvation.

Many years later, Russian cultural propaganda would make the fate of the great writer seem even more unfair and tragic, surrounding Gogol’s legacy with an unkind layer of speculative mysticism. In the cultural consciousness, Gogol is inscribed as a madman driven astray by his own unholy creations. I remember hearing variations of this narrative from my mother and my teachers. Many years later when I researched Gogol’s biography and confronted my mother about this, she shrugged - “this is what people were saying”.

It was an enduring public rumor that Gogol started seeing the devils and dark entities he was writing about (how Lovecraftian), and that these visions drove him to delusional paranoia. This myth is further supported by literal reading into the words Gogol uttered shortly after burning the second draft of the Dead Souls manuscript. He claimed he didn’t mean to burn the draft, but did so under the influence of the “evil spirit”.

Gogol’s fate is tragic for many reasons. For once, it illustrates a trajectory of a creator falling further from authenticity (Gogol’s cultural identity) and tasking himself with reforming the very culture that instigates and supports the fall from authenticity in order to fragment populations and re-assert its imperialist cultural narrative. This is an impossible task to hold oneself accountable to. But prior falling victim to such impossible tasks, Gogol gave us the world that was full of wonder - the world where the laws and scriptures were meaningless, the world where the cultural lifeblood of the folklore rebelled against the fruitless attempts to constrain it. The world of Ukraininan gothic.

Defiance in Sips

Seeing my sudden obsession with Gogol that seemingly resurfaced out of nowhere, my mother reminded me of something I had long forgotten. At the age of eleven, while we still lived in Russia, I enrolled in a national literary conference. The rules were simple but demanding: participants were required to read the complete works of a single author (participant’s choice), write an essay on their chosen subject, and present it to an audience. I was the youngest participant of my group. And yet, there I was, faithfully reading Gogol’s entire literary catalogue, complete with “mature” pieces like Dead Souls. At the time, my mother was quite surprised - both at my unwavering determination, and at the quality of my work.

As she kept talking, I started vaguely recalling the situation. Despite countless hours spent reading, writing, and preparing - stacked atop the demands of schoolwork - I was ultimately barred from advancing to the regional level of the competition. At this point I asked my mother if she remembered why I haven’t passed the regional competitions, thinking to myself that at eleven years old, my writing likely wasn’t at the level expected for such things. My mom smiled faintly, almost conspiratorially, and said, “I think you wrote something they weren’t really interested in reading.” She left it at that. I don’t remember what I wrote more than twenty years ago - we didn’t keep the drafts. But if you love writing - you definitely should, for this world would be better with more writing in it.